(Huffington Post) In late January, shortly after President Barack Obama began his second term, Navy Cmdr. Walter Ruiz stood inside an old airplane hangar on the southernmost tip of the island and reflected on a central but unfulfilled promise of Obama’s 2008 campaign.

“We’re still here,” Ruiz said, as reporters milled around the aging hangar, which has been repurposed as a work space for the journalists and human rights observers who have been flying in and out of Guantanamo since the first suspected terrorists were brought here 11 years ago. Instead of planes, the hangar is now home to several trailer-size sheds with slanted roofs. More offices line the hangar’s perimeter, and a giant map of the base is painted on the floor. Screeching bats fly in and out of the hangar at night.

“We’re still in military commissions. We’re still arguing about the basic protections the system affords us. We’re still talking about indefinite detention,” Ruiz continued. “We’re still talking about not closing the facility.”

After years of legal wrangling, the trials of Khalid Sheikh Muhammad and four other men allegedly responsible for the 9/11 attacks have barely gotten off the ground. Ruiz, an attorney for alleged 9/11 organizer and financier Mustafa Ahmed Hawsawi, estimates he has traveled to Guantanamo 50 to 100 times for client meetings and pre-trial hearings on legal minutiae since he joined the military’s defense counsel office in September 2008.

“I’m here trying this case, people were here trying this case in 2008, arguing many of the same motions we’re arguing now,” Ruiz said. “And I think folks that have been around here for a while would tell you not much has changed at all.”

During his first campaign for the White House, Obama pledged to end an ugly chapter in American history and prove to the world that the United States could safeguard the country from terrorism without sacrificing its commitment to freedom and liberty.

“In the dark halls of Abu Ghraib and the detention cells of Guantanamo, we have compromised our most precious values,” Obama declared in a speech on Aug. 1, 2007. In one of his first acts upon taking office in January 2009, the president, flanked by admirals and generals, directed the military to close the prison camp here within a year.

Today, however, the detention center at Guantanamo appears less likely than ever to close. There are 166 people currently imprisoned, down from a high of 684 in 2003. But those who remain are likely to do so indefinitely. Effectively banned from the continental U.S. by Congress, disowned by their home countries and unwelcome pretty much everywhere else, they have no place to go.

Today, however, the detention center at Guantanamo appears less likely than ever to close. There are 166 people currently imprisoned, down from a high of 684 in 2003. But those who remain are likely to do so indefinitely. Effectively banned from the continental U.S. by Congress, disowned by their home countries and unwelcome pretty much everywhere else, they have no place to go.

In addition to the seven Guantanamo detainees currently facing charges — including the five charged in relation to the 9/11 attacks — 24 may face charges in the future. Three current detainees have already been convicted in military tribunals: one was sentenced to life in prison, one is scheduled to be released pending testimony in another case and one has had his sentencing delayed for four years.

Of the rest, however, the U.S. has designated 86 detainees for release but can’t actually set them free. Thirty are from Yemen, and the U.S. won’t send them back there while it remains a hotbed of terrorism. No country is willing to accept the others. And it’s a political nonstarter to release them into the U.S.

In 2010, Obama’s Guantanamo Task Force determined that another 46 were “too dangerous to transfer but not feasible for prosecution.” And so they remain stuck here, in limbo.

Obama has periodically reiterated his intention to close the detention center, most recently during an appearance on “The Daily Show” with Jon Stewart in October. But the public pressure on him to do so has largely died down, as tales of detainee abuse at the hands of CIA interrogators fade into the past and the media turns its attention to new fronts in the war on terrorism, such as the administration’s drone program.

The truth is that nobody is really in a hurry to close Guantanamo. Defense attorneys, whose ultimate goal is to keep their clients alive, certainly aren’t in a rush, and have adopted a strategy of throwing up procedural objections that often slow the court’s already glacial pace. Prosecutors, anxious to avoid any possible legal challenges that could come up on appeal, are moving deliberately to make sure they’re dotting every “i” and crossing every “t.” Last month, the Obama administration shuttered the State Department office tasked with planning Guantanamo’s closure.

As a result, the vague idea of indefinite detention is looking more specifically like life in prison, at least for those detainees who are not sentenced to death by the military commissions. And with the youngest detainee still in his 20s, Guantanamo could conceivably remain open for decades to come.

‘HAVE A GOOD TIME’

It’s no surprise, then, that as Obama’s second term begins, Guantanamo seems to be putting down roots. Indeed, parts of the naval base have taken on the appearance of a new beachside housing development. Hundreds of homes are currently under construction in neighborhoods with names like Iguana Terrace and Marina Point, to house the growing population of military personnel, civilian contractors and their families, which currently stands at approximately 5,000.

The base features a Starbucks, a Subway, a McDonald’s, a KFC/Taco Bell, a supermarket, a golf course, a restaurant serving Jamaican jerk chicken and an Irish pub. A gift shop sells stuffed iguanas and T-shirts emblazoned with Guantanamo Bay slogans like “Close, But No Cigar.”

Fidel Castro bobbleheads are one of the most popular items for sale at the base’s radio station, Radio GTMO, which broadcasts popular tunes like PSY’s “Gangnam Style”. Cuban music bleeds over from stations on the other side of the island.

Improvements have also been made to the areas of the base that house the detainees. The Bush administration quickly replaced the temporary Camp X-Ray with more permanent facilities in 2002, after photos emerged of detainees in orange jumpsuits sitting in chain-link holding pens, causing an outcry from human rights groups and criticism from around the world. In 2011, the Obama administration added a new soccer field for some of the cooperative detainees, along with covered walkways that allow them to move between cellblocks unescorted.

The joke around Gitmo is that the detainees enjoy nicer facilities than the guards, who live in temporary metal trailers scattered all over the base. But the guards, too, may soon get an upgrade. The commander of the base, Capt. John Nettleton, recently told Reuters that he wants to build a new cafeteria for the camp’s personnel, along with a permanent barracks.

Some of the most significant changes have taken place at Camp Justice, the section of the base that houses the court facilities and the tent city for visiting lawyers, human rights observers, journalists and court officials. The Bush administration had proposed a major $125 million expansion, including a new courthouse and a hotel to replace the tent city. Congress balked at the project, however, and then-Defense Secretary Robert Gates quickly condemned it. The $12 million substitute, technically a temporary facility, was completed in 2008.

The windowless, barn-like structure looks like something that might hold a high-school basketball court, and is surrounded by layers of barbed-wire fences. Inside, however, it is state of the art, featuring a soundproof spectator gallery, digital document displays for lawyers and audio speakers under the table that broadcast Arabic translations of the proceedings for defendants who refuse to wear headphones. Whereas the old courthouse held a single, cramped courtroom, the new facility has space to try up to five defendants at once.

Visiting defense attorneys now stay in new townhouse condos, but journalists and observers remain relegated to Camp Justice’s tent city. In the airplane hangar, there is an “internet cafe” where human rights observers have set up an office. “We now have a printer this time, which we’ve been asking for for a while,” said Laura Pitter, a counterterrorism adviser with Human Rights Watch. “We have a working phone in there now. We didn’t have a working phone last time.”

In addition to his official portrait, visible in a few locations around the base, there are other subtle reminders that Obama is now in charge. The tents at Camp Justice are outfitted with energy-efficient light bulbs. The cover of “The Wire” — the newsletter of Joint Task Force Guantanamo, the entity which runs GTMO’s prisons — features a photo of Obama’s ceremonial swearing in at his second inauguration. A military spokesman who travels with reporters to Guantanamo is married to another man.

In addition to his official portrait, visible in a few locations around the base, there are other subtle reminders that Obama is now in charge. The tents at Camp Justice are outfitted with energy-efficient light bulbs. The cover of “The Wire” — the newsletter of Joint Task Force Guantanamo, the entity which runs GTMO’s prisons — features a photo of Obama’s ceremonial swearing in at his second inauguration. A military spokesman who travels with reporters to Guantanamo is married to another man.

There have been victories for members of the media. New divider walls give journalists a bit more privacy in their heavily air-conditioned six-person tents. Reporters are now allowed to roam around parts of the base without an escort and no longer have a curfew — privileges that journalists embedded with the military in Iraq and Afghanistan have enjoyed for years but were absent at Guantanamo until last month. In January, visiting journalists were given a tour of one of the holding cells located next to the courtroom facility for the first time in years.

“Have a good time,” a young guard told the reporters about to tour the cell, after scanning them for metal or electronic devices.

Unlike the Bush administration, the Obama administration has been relatively hands off when it comes to media restrictions at Guantanamo, letting officials on the ground set the rules.

Still, it was under Obama that four reporters, including Miami Herald reporter Carol Rosenberg, widely considered the dean of the Guantanamo press corps, were banned from Guantanamo for life in May 2010 for disclosing the name of a witness whose identity is under a protective order, despite the fact that his name was already public. The reporters fought the ban, and the Pentagon overturned it that July.

The new courthouse, in many ways, is the end result of a long debate about how to try the detainees. The Bush administration — which housed the suspected terrorists at Guantanamo in order to avoid the due process required under the U.S. criminal justice system, as well as the Geneva conventions’ prohibitions on torture — adamantly opposed the idea of trying them in U.S. courts. The Supreme Court has ruled, however, that foreign terrorism suspects do have the right to challenge their detention in U.S. courts.

Obama shut down the military tribunals as soon as he took office and began exploring ways to transfer the suspected terrorists to American soil — possibly to a prison in Illinois — and try them in federal courts. Throughout the long, hot summer of 2009, however, as the Tea Party movement blossomed, Republicans charged that closing Guantanamo would put Americans in danger, potentially even leading to terrorist prison breaks. Senate Democrats, lead by Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-Nev.), also opposed transfering the detainees and cut off $80 million Obama had requested to do so, claiming the administration had done too little to outline its plans.

Andy Worthington, a journalist and activist who has been writing about the camp for seven years, said that Congress, which has repeatedly prevented Obama from using federal money to transfer any detainees out of Guantanamo, shares some of the blame for the camp’s continued existence. Reid, who recently claimed it was “nobody’s fault” that Guantanamo had not been closed, is “part of the absolute failure,” Worthington said.

Reid did not respond to a request for comment.

At Guantanamo, some members of the military are quick to point out that the Pentagon didn’t seek out the duty of trying terrorists in the tribunal system, but that it was rather a burden imposed on the military by Congress. “They should really call them congressional commissions instead of military commissions,” one officer joked.

But ultimately, Worthington said, Obama will have his name attached to the camp, just as Bush’s was.

“He will go down in history fairly clearly as the man who failed to close this abomination,” Worthington said. “They will judge that President Obama failed to close it pretty much because he ran up against political difficulties.”

“I think that Obama did not want to invest the political capital in it to take the steps necessary to make it happen,” Pitter said.

THE ‘RE-BRANDER’

Unable to close Guantanamo, Obama restarted the military commissions in March 2011. He did succeed, however, in reforming them to a certain extent, increasing transparency and bringing their policies and handling of evidence closer in line with U.S. courts. But the legality of the commissions is still being debated, and the detainees may appeal any verdicts in federal court, setting up a prolonged battle that will likely wind its way back to the Supreme Court.

For now, Brig. Gen. Mark S. Martins is the man with the difficult task of selling the world on the legitimacy of the proceedings. Martins took the job of chief prosecutor in October 2011, and he is a staunch defender of trying the detainees in military commissions as opposed to federal courts.

“There are narrow but important differences, and this often gets lost when I talk about federal courts, because someone will say, ‘Hey, he should try to just mimic federal courts, why do you need [military commissions]?'” Martins said, sitting in a bare-bones office in the old court building at the top of the hill overlooking the new courthouse. “This just fuels the argument about how, why are they necessary? The differences are important.”

Miranda rights don’t apply in military commissions — statements just need to be determined to be voluntary in order to be included as evidence. There are also looser rules on hearsay statements. Martins said the distinctions between U.S. courts and the military commissions could be “decisive in certain cases.”

Miranda rights don’t apply in military commissions — statements just need to be determined to be voluntary in order to be included as evidence. There are also looser rules on hearsay statements. Martins said the distinctions between U.S. courts and the military commissions could be “decisive in certain cases.”

The reformed military commissions are designed to address some of the concerns of both the U.S. government and human rights advocates. Any statements obtained as a result of torture or cruel or degrading treatment are prohibited. Detainees have greater access to classified information that might be relevant to building their defense cases. Journalists have increased standing before the court.

“Anyone who was familiar with the process before and looks at it now, I think, is looking fairly at it, would say there’s a significant proportion more of this proceeding that we can look at, understand, analyze,” Martins said.

Demonstrating that transparency has proven difficult at times, however. Last month, in the first day of hearings in the 9/11 case, an anonymous censor cut off the closed-circuit TV feed of the proceedings that members of the media were watching. Normally, the judge and the court security officer could censor information they feel should remain classified. But neither had moved to censor the information in this instance, leaving journalists and defense lawyers to infer that the CIA was secretly pulling the strings behind the scenes and undermining the commission’s established rules.

The judge ordered the outside censor button removed, but the controversy ate up most of the week’s proceedings, even bleeding into a separate hearing involving a defendant charged in connection with the attack on the USS Cole in October 2000, as defense attorneys questioned whether they could ethically continue if they believed their communications were being monitored. Two weeks later, when the hearings reconvened, lawyers were still debating issues involving the monitoring of communications that the incident raised.

Similarly, Martins has sought to dismiss charges against a number of detainees that he feels are not sustainable under international law, only to be overruled by the more senior Pentagon officials who oversee the military commissions.

Martins told HuffPost that, to him, the dispute over the charges is about “principled disagreements” between government officials carrying out their duties “honorably and faithfully under the law.” Critics, however, say it shows that the reforms to the commissions system are just cosmetic changes to a fundamentally flawed tribunal process.

“Some people call him the ‘re-brander.’ He was going to come in here, he was going to lend his name, his rank, his stature, and legitimize this process,” Ruiz said of Martins. “Now you have that person talking to another official and telling him, ‘I think this is a bad idea. I think we need to remove these charges because it will remove the legal uncertainty moving forward.’ And you have this non-entity — which is not a party, not a prosecutor, not a defense counsel, he’s not a judge — who says, ‘No, I’m not going to do it.'”

“That alone is remarkable,” said Ruiz.

“What happens when he’s not here?” asked Human Rights Watch’s Pitter, who similarly praised Martins for bringing the military commission procedures closer in line with those of federal courts. “What happens when there’s a prosecutor who is going to use all the rules at his disposal for a commission like this?”

Martins, who is 52 and has deferred promotion and retirement to continue in his role as chief prosecutor at Guantanamo, said he’s in it for the long haul. “We’re making progress,” he insisted.

“I’m here as long as it takes,” Martins said. “This is my last job in the military. I’ve gotten word that although my retirement date would have been November of 2014, it can actually be years, well after that. I’m committed to this.”

Just a little over a year ago, President Obama signed an Executive Order titled

Just a little over a year ago, President Obama signed an Executive Order titled

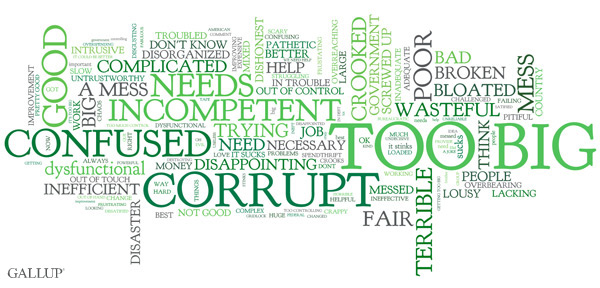

(fromthetrenchesworldreport.com) The communist insurgents within the United States continue their push to disarm we American nationals, even to the point of presenting poll numbers which have been proven to be false via their own previous admissions. Captain Mark Kelly, the husband of ex-Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords, was making the rounds over the weekend, spouting his sedition while trying to present himself as some kind of American hero.

(fromthetrenchesworldreport.com) The communist insurgents within the United States continue their push to disarm we American nationals, even to the point of presenting poll numbers which have been proven to be false via their own previous admissions. Captain Mark Kelly, the husband of ex-Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords, was making the rounds over the weekend, spouting his sedition while trying to present himself as some kind of American hero.

In its report, the commission recommended that federal judges give sentencing guidelines more weight, and that appeals courts more closely scrutinize sentences that fall beyond them.

In its report, the commission recommended that federal judges give sentencing guidelines more weight, and that appeals courts more closely scrutinize sentences that fall beyond them. Today, however, the detention center at Guantanamo appears less likely than ever to close. There are 166 people currently imprisoned, down from

Today, however, the detention center at Guantanamo appears less likely than ever to close. There are 166 people currently imprisoned, down from  In addition to his official portrait, visible in a few locations around the base, there are other subtle reminders that Obama is now in charge. The tents at Camp Justice are outfitted with energy-efficient light bulbs. The cover of “The Wire” — the newsletter of Joint Task Force Guantanamo, the entity which runs GTMO’s prisons — features a photo of Obama’s ceremonial swearing in at his second inauguration. A military spokesman who travels with reporters to Guantanamo is married to another man.

In addition to his official portrait, visible in a few locations around the base, there are other subtle reminders that Obama is now in charge. The tents at Camp Justice are outfitted with energy-efficient light bulbs. The cover of “The Wire” — the newsletter of Joint Task Force Guantanamo, the entity which runs GTMO’s prisons — features a photo of Obama’s ceremonial swearing in at his second inauguration. A military spokesman who travels with reporters to Guantanamo is married to another man.

Miranda rights don’t apply in military commissions — statements just need to be determined to be voluntary in order to be included as evidence. There are also looser rules on hearsay statements. Martins said the distinctions between U.S. courts and the military commissions could be “decisive in certain cases.”

Miranda rights don’t apply in military commissions — statements just need to be determined to be voluntary in order to be included as evidence. There are also looser rules on hearsay statements. Martins said the distinctions between U.S. courts and the military commissions could be “decisive in certain cases.”

Republican Florida State Senate President Don Gaetz showed the true face of tyrannical RINOs in the Republican Party when he openly laughed and mocked the Constitutional principles espoused by KrisAnne Hall, an attorney and former prosecutor, who supports the Tenth Amendment and the right of the States to nullify unconstitutional laws implemented by the federal government. However, it appears that Mr. Gaetz also indicated his support of the tactic of the seventh President of the United States Andrew Jackson in how he would deal with “nullifiers.” He would have them shot and hanged.

Republican Florida State Senate President Don Gaetz showed the true face of tyrannical RINOs in the Republican Party when he openly laughed and mocked the Constitutional principles espoused by KrisAnne Hall, an attorney and former prosecutor, who supports the Tenth Amendment and the right of the States to nullify unconstitutional laws implemented by the federal government. However, it appears that Mr. Gaetz also indicated his support of the tactic of the seventh President of the United States Andrew Jackson in how he would deal with “nullifiers.” He would have them shot and hanged.